The Misconception: You should focus on the successes if you wish to become successful.

The Truth: When failure becomes invisible, the difference between failure and success may also become invisible.

Plumis was founded on the back of a research project at Imperial College London and the Royal College of Art in 2008. After talking to firefighters from our local brigade, William and I were inspired to come up with new ways to protect vulnerable people in their homes.

What we believed and what quickly became our philosophy, was that if we focused on developing solutions for the most vulnerable individuals in our society, then our solutions would be better placed to provide adequate protection for more people, if not everyone. Only then, would we be able to truly reduce the number of deaths and injuries from fire.

We started by collecting the latest data and information available on fire safety, reviewing it with a fresh pair of eyes to understand the current challenges and issues. It was through this process, we decided to undertake a survivorship bias analysis so we could then identify the areas where we believed we could make the most impact and apply our creative techniques to come up with new and innovative solutions.

What is Survivorship bias?

Survivorship bias describes the tendency to focus on the people or things that have passed some kind of selection process, overlooking those that did not and therefore drawing false conclusions.

Survivorship bias describes the tendency to focus on the people or things that have passed some kind of selection process, overlooking those that did not and therefore drawing false conclusions.

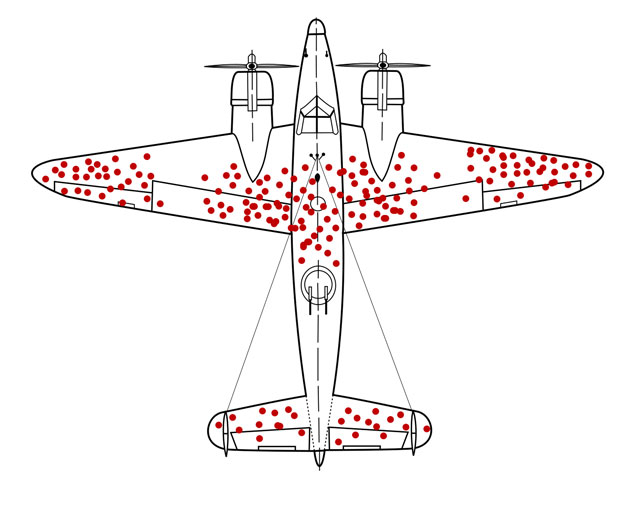

A famous example of survivorship bias dates back to World War II, when mathematician Abraham Wald was asked by the American military to study how best to protect their aircraft from being shot down.

Whilst armour could support the military in achieving this, the material was too heavy to cover the whole plane and would negatively impact its flying capability.

Their plan, therefore, had been to examine the planes returning from combat, see where they were hit the worst – the wings, around the tail gunner and down the centre of the body – and then reinforce those areas. However, Wald took survivorship bias into his calculations, recommending that the additional armour should be applied to the areas that showed the least damage.

Wald reasoned that the military had only considered aircraft that had survived their missions; any that had been shot down or otherwise lost had logically been deemed as unavailable for assessment. The bullet holes in the returning aircraft areas actually indicated the areas a plane could be hit and keep flying – exactly the areas that did not need reinforcing.

Traditional fire sprinkler performance data

We decided to incorporate survivorship bias thinking into our own examination of fire sprinkler data. Most studies, and rightly so, highlight the significant and positive contribution of fire sprinklers saving lives and increasing property safety across a broad range of building types and fire scenarios. However, we wanted to see if we could find any ‘invisible failures’ that had been overlooked that we could try to tackle.

For example, the U.S. Experience with Sprinklers, July 2017’ states:

‘Sprinklers operated effectively in 88% of the fires large enough to activate them.’

This triggered us to ask two questions. The first being were there any negative consequences, as a result of the fires not large enough to activate sprinklers? The second was whether anything can be done to reduce injuries and fatalities in fires where sprinklers were activated?

Similar questions were also being raised in other studies across the UK. For example, An Analysis from Fire Service Data Incidence of Deaths and Injuries in Sprinklered Buildings: A Supplementary Report March 2019’, concluded:

‘3,046 buildings fires were recorded where sprinklers were present. Sprinklers were recorded as having activated in 1300. Of these 1300 fires, there were 156 recorded casualties. Five fatalities occurred in premises where a fixed system was present. All of these were in dwellings.’

Further investigation into the five fatal dwelling fires, where sprinklers were present, found that the circumstances of the fire fell outside the life-saving operating parameters of the system’s design.

Typically, the individual was directly involved in the fire with either their clothing or bedding catching fire, which was commonly caused by smoking materials. A large proportion of casualties were also found to have impacted those who had reduced or limited mobility, rendering them either incapable of easily removing the affected clothing or moving away from the fire itself. Having many medical comorbidities also significantly increased peoples risk of injury, including burns or smoke inhalation, and fatality.

The design parameters of sprinklers

Traditional fire sprinklers are designed to operate when affected by the heat from a fire. Most sprinkler heads feature a glass bulb filled with a glycerin-based liquid, which expands when it comes into contact with heated air, shattering the glass and activating the sprinkler head.

Sprinklers are most effective at tackling fast-growing fires, like an old sofa fire, as the activation temperature threshold is breached quickly minimising the time for toxic gas production. When activated, sprinklers can prevent flashover – one of the most-feared phenomena among firefighters – it is the near-simultaneous ignition of most of the directly exposed combustible material in an enclosed area.

Preventing or delaying flashover is pivotal, but the time it takes before a fire creates enough heat to operate a sprinkler (if at all, if the fire is outside its operating parameters) is also critical when the protection of vulnerable occupants is at stake.

In 2019/20, thankfully only 7% of the 775 fires in purpose-built high-rise flats spread beyond the room of origin. In part, this is due to effective compartmentation between rooms, as well as early reporting and response by the authorities. Nonetheless, the most common cause of death for fire-related fatalities was ‘overcome by gas or smoke’, reported for 30% (73) of fire-related fatalities.

All combustible materials produce some form of toxic smoke when they burn but how much toxic smoke will be emitted depends on the material, the amount of oxygen available and how long it burns. The risk can vary significantly depending on the health and age of the occupant.

A single exposure to toxic gases from a house fire can have severe long-term effects that may occur immediately and clear up after a few days or may result in a permanent injury.

Although it can be complicated trying to distinguish between casual effects and coincidental illnesses, there is a wide range of possible long-term effects that can result from smoke inhalation.

A reduced supply of oxygen (hypoxic episode) can result in someone being unconscious and then recovering after oxygen treatment, to some degree of permanent brain damage. Mineral particles or fibres are released in a fire that can result in permanent lung damage, and even cancer some years following a single incident. Many are calling for more research into these long-term effects, and we must ensure these factors do not go ignored or become invisible.

So, our analysis gave us a clear and important target area to examine:

- How do we ensure that we limit an individual's exposure to smoke during a fire?

- How do we ensure we have solutions that can address slow-growing fires, which can be the case with electrical fires? This is particularly important considering in August 2020, Electrical Safety First reported that the number of accidental electrical fires in tower blocks has risen in each of the last three years, from 301 in 2016-17 to 355 in 2018-19.

- What if the fire remains small but produces lethal amounts of toxic smoke?

The case for smarter solutions

A recent briefing paper by The Building Research Establishment, ‘The causes of fire fatalities and serious fire injuries in Scotland and potential solutions to reduce them - Phase 1: IRS review’, found that current technologies and approaches may provide insufficient protection for vulnerable occupants and made 14 recommendations, including increasing the use of combined detection and suppression watermist systems.

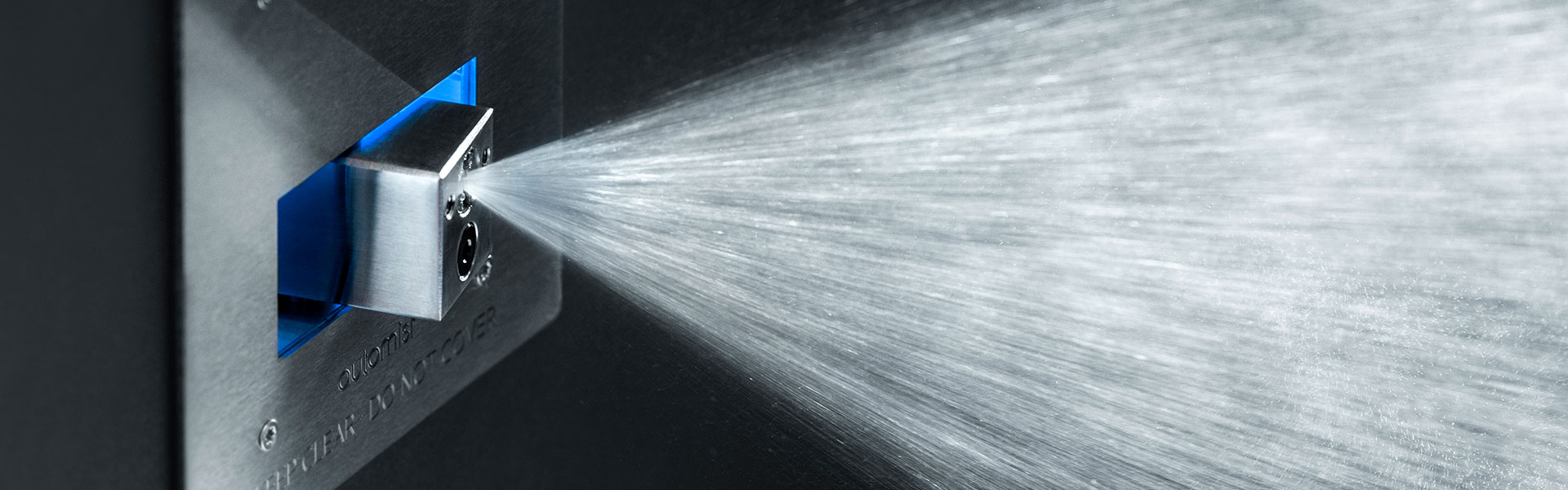

Automist activates electronically overcoming the constraints of existing sprinkler systems by operating earlier, before the temperature required to burst the glass bulb of a sprinkler, and tackling fires before they generate that amount of heat, helping to reduce smoke and maintain survivable conditions.

Our award-winning active fire suppression system (AFSS) is being retrofitted in 329 social homes in the London Borough of Lambeth. The project is being delivered with minimal disruption to residents and is designed to increase fire protection for some of the council’s most vulnerable residents.

There are two key components of our innovative solution:

- A reliable integrated early warning smoke and heat combination alarm is part of every installation to raise the alarm long before the fire starts to emerge. This sensor can be coupled with a communications device for remote monitoring to inform a responsible person or call for help.

- An infrared sensor to detect the fire using our proprietary, intelligent fire detection algorithm.

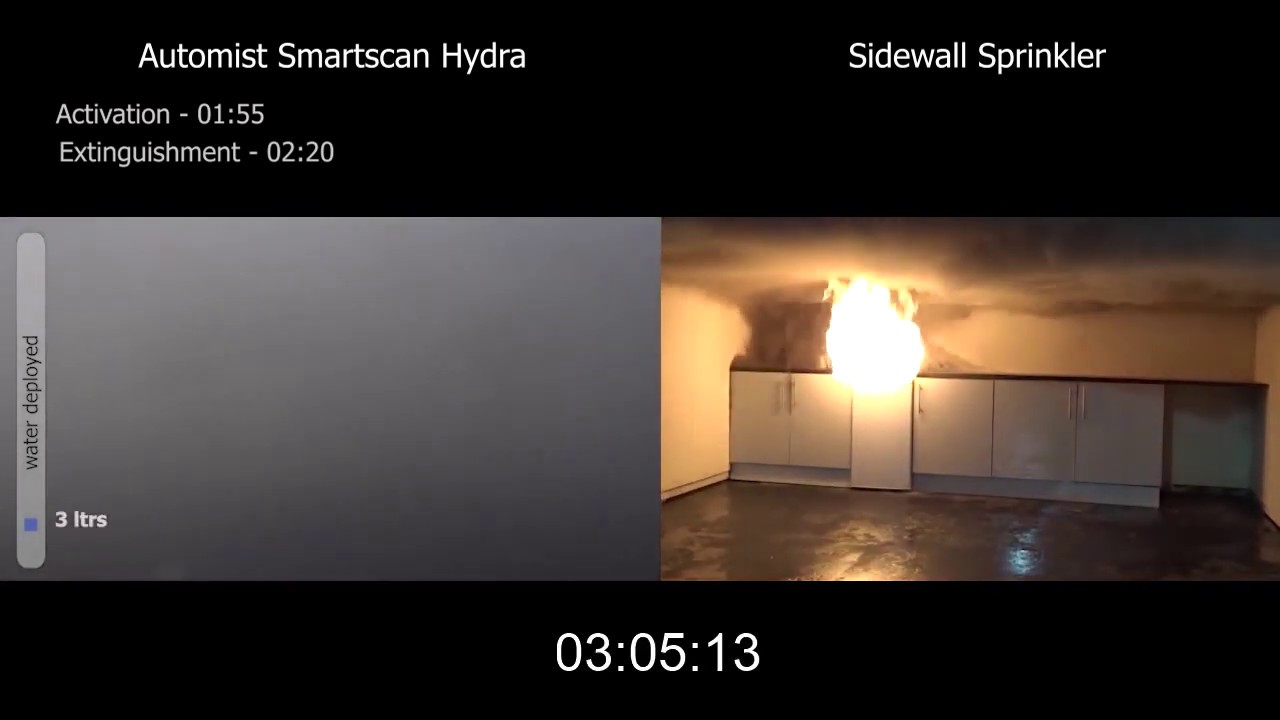

In 2019, Plumis conducted a series of tests at the Burn Hall at the Fire Protection Association (FPA) to see how the Automist Smartscan system compared to other fire suppression products. Testing showed that for a challenging concealed fire, such as a fridge, the system activated almost two minutes earlier than a traditional sprinkler:

We are working hard to keep improving the performance of our system for a broad range of fire types, but we believe early and reliable activation is the key to improving life safety and property protection. We worked with Dr Charlie Hopkin and Dr Michael Spearpoint to examine how an electronically controlled nozzle system performs compared to traditional sprinkler systems and consider its impact on hazards that are not currently captured in existing standard test methods. We created "some tests for refrigerator fires which burn significantly slower and with more smoke output than the fire source used to assess suppression systems within standards" and concluded, for the specific experiments presented in our research, the measured activation times of a concealed sprinkler head are 2.0–13.7 times slower than those using an electronic nozzle system.

Wald’s brilliantly simple observation completely changed the approach the military took towards armouring their planes, and no doubt saved lives. At Plumis we aim to do the same, by analysing both the successes and the failures hidden within the data. In this instance, fires are the shells damaging the plane and detection and suppression, including sprinklers, being the armour.

The fire industry has tended to focus on examples of sprinklers successfully putting out fires that provide a valuable contribution to fire safety, but we must not ignore the types of fire and occupancy where they do not perform well or risk not performing at all. By examining the whole picture, we can find new solutions to complement the old ones, further enhance fire protection and save more lives.

Written by Plumis co-founder and inventor of Automist, Yusuf Muhammad. To learn more about Automist watch a webinar (video available anytime), or review our interactive explainer.